Sérgio Palma Brito

Capítulo 1

INTRODUÇÃO à HISTÓRIA do VIAJAR e à FORMAÇÃO do TURISMO em PORTUGAL

...

Durante o período que vai de meados dos anos 50 do século XX à crise de 2008-2009, concentramo-nos na formação da oferta de turismo resultante da procura massificada e sazonal da viagem para estanciar durante o tempo livre. É esta oferta de turismo que está no cerne da relação entre turismo, ambiente e ordenamento do território, a qual constitui a base do conceito de sustentabilidade.

A política e a administração do turismo começam por se preocupar com o turismo cultural, urbano e termal e, numa menor dimensão, com o das praias. A partir do início dos anos 60 do século XX, a mutação da oferta de turismo, sobretudo no Algarve, coloca novos problemas quanto à sua relação com esta última oferta de turismo (com destaque para o turismo residencial) e com a política e a administração do ordenamento do território e do ambiente.

...

Urbanização Turística

Anos 60 a 90: Urbanização Turística Dispersa

«Urbanização turística» designa a concentração crescente das populações que podem viajar para estanciar durante o tempo livre em estâncias ou zonas de turismo (no passado), e em núcleos turísticos, núcleos e urbes urbano-turísticas e edificação dispersa, integrados ou não numa área turística (no presente).

Entre os anos 60 e 90 forma-se no Algarve uma urbanização turística dispersa, caso especial da urbanização dispersa que então prolifera por todo o País, com edificação legal ou clandestina, e que está na origem de parte das actuais fraquezas da urbanização em Portugal. É a primeira patologia do povoamento urbano do Algarve, utilizando-se o termo «patologia» no sentido económico, social e político de «excessos de uma prática a que falta regulação», e não no sentido biológico.

Durante cerca de um quarto de século, esta urbanização turística dispersa compreende duas formas distintas:

► O «núcleo turístico fora dos perímetros urbanos», com urbanismo turístico em «ambiente de resort», criado na maior parte dos casos pela urbanização estruturada de propriedades cuja área varia entre alguns hectares e os 16 km de Vilamoura. Estes núcleos passam por processos de expansão orgânica («arredondamento»), de densificação das áreas iniciais e de reconversão estruturante (caso de Vilamoura em Vilamoura XXI);

► O «núcleo urbano-turístico», resultante da transformação dos núcleos urbanos da vilegiatura tradicional, por expansão orgânica para a periferia ou densificação da edificação urbana no seu seio, ou por ambos os processos. Alguns destes núcleos formam-se a partir de aglomerados piscatórios que, dada a sua irrelevância, não são sequer objecto do planeamento urbanístico anterior a 1962.

Datam também desta altura:

►

a edificação dispersa de utilização turística, de que são exemplo as moradias construídas no Cerro da Águia, a poente de Albufeira;

► aquilo que, dezenas de anos mais tarde, se designará por estabelecimentos hoteleiros isolados ...

A urbanização turística integra dois tipos de espaços cuja dinâmica é inseparável do turismo residencial:

► A prática do golfe ...;

► As marinas ...

Ruptura Política dos Anos 90 e Novas Formas de Urbanização Turística

A ruptura política dos anos 90 está na origem de duas novas formas de urbanização turística. A primeira assenta na consolidação da urbanização turística dispersa e compreende duas dinâmicas similares, mas diferentes na escala:

► A consagração da expansão de «núcleos urbano-turísticos» preexistentes, pela definição de perímetros urbanos mais ou menos generosos – um processo que ultrapassa, em muito, os limites do Algarve e de que são exemplo os núcleos

de desenvolvimento turístico do PROTALI de 1993;

► No Algarve, começam a formar-se quatro «urbes urbano-turísticas» (do Alvor

a Praia da Rocha, Armação de Pêra e Albufeira e de Vilamoura a Quarteira) que se distinguem pela sua escala e pela formação, a norte, de largas frentes de mar, segundo dois movimentos: a expansão orgânica do núcleo urbano-turístico inicial; e a integração de outros focos da dinâmica urbana dispersa, localizados a poucos quilómetros deste núcleo.

Na sub-região do litoral do Algarve, a escala da procura faz com que estas quatro urbes e uma consolidação mais intensa nos «núcleos urbano-turísticos» contribuam para formar uma economia turístico-residencial única em Portugal. Encontramos algo deste modelo na urbanização que actualmente vai dos Estoris até à Guia, no concelho de Cascais.

A segunda forma de urbanização turística é a dos núcleos turísticos de nova geração. Estes núcleos são uma nova e mais sofisticada forma do «núcleo turístico fora dos perímetros urbanos» após quase 30 anos de urbanização turística dispersa.

Edificação Dispersa

A edificação dispersa é um problema em várias regiões do País, sendo utilizada para residência permanente ou casa para viver o tempo livre com a possibilidade de alternar ou conciliar estas utilizações. A vivência do tempo livre começa por ter lugar na proximidade dos grandes centros urbanos (onde nasce a designação de «casa de fim-de-semana») ou em áreas turísticas cujo exemplo mais significativo é o Algarve.

No caso do Algarve da actualidade, edificação dispersa designa a transformação da dinâmica de dispersão e concentração de «habitações dispersas» do povoamento rural do Algarve de 1962 pela utilização como casa do tempo livre ou residência permanente da população local. Inclui a recuperação de habitação da população rural e novas edificações cujo licenciamento assenta em criativas interpretações das disposições legais que pretendem limitá-la ou proibi-la.

Esta definição de edificação dispersa não inclui a aparente dispersão física das moradias de um conjunto urbanístico (Vilamoura ou Quinta do Lago), nem a edificação dispersa de cariz suburbano e mais concentrada verificada na proximidade de uma cidade; e é diferente da morfologia de empreendimento de turismo residencial, que designamos por «estruturação da exploração de moradias dispersas».

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.spi.pt/turismo/Manuais/Manual_II.pdf

30 de agosto de 2012

29 de agosto de 2012

Darkness on the Edge of Town: Mapping Urban and Peri-Urban Australia Using Nighttime Satellite Imagery

Paul C. Sutton and Andrew R. Goetz - University of Denver

Stephen Fildes and Clive Forste - Flinders University, Australia

Tilottama Ghosh - University of Denver

This article explores the use of nighttime satellite imagery for mapping urban and peri-urban areas of Australia. A population-weighted measure of urban sprawl is used to characterize relative levels of sprawl for Australia’s urban areas. In addition, the expansive areas of low light surrounding most major metropolitan areas are used to map the urban–bush interface of exurban land use. Our findings suggest that 82 percent of the Australian population lives in urban areas, 15 percent live in peri-urban or exurban areas, and 3 percent live in rural areas. This represents a significantly more concentrated human settlement pattern than presently exists in the United States.

Urban Decentralization Processes

Methods

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

Nighttime satellite imagery has been used to map urban and an exurban population in the United States and this article demonstrates that the same methods are reasonable for mapping similar urban and exurban environments in Australia. Comparing these results with prior studies of U.S. cities shows that Australia is significantly more urban than the United States and Australia’s urban areas do not sprawl in either an urban or peri-urban way relative to those in the United States. Within Australia, Sydney sprawls the least and Brisbane sprawls the most. Perth sprawls a bit, but Melbourne and Adelaide do not. Comparing the peri-urban populations and areal extent of these five big cities is problematic due to the differing degree of conurbation they have with nearby large cities (e.g., Sydney with Newcastle and Woo- longong; Brisbane with the Gold Coast; Perth with Freemantle and Mandurah; Melbourne with Geelong; and Adelaide with Mt. Barker). Future demographic, economic, social, political, and ethical decisions and nondecisions will determine whether Australia will move toward or away from the urban and exurban sprawl that presently exists in the United States.

Literature Cited

in:

Sutton, Paul C., Goetz, Andrew R., Fildes, Stephen, Forster, Clive and Ghosh, Tilottama(2010) 'Darkness on the Edge of Town: Mapping Urban and Peri-Urban Australia Using Nighttime Satellite Imagery', The Professional Geographer, 62: 1, 119 — 133, First published on: 11 December 2009 (iFirst)

link para o texto integral:

http://urizen-geography.nsm.du.edu/~psutton/AAA_Sutton_WebPage/Sutton/Publications/Sut_Pub_9.pdf

Stephen Fildes and Clive Forste - Flinders University, Australia

Tilottama Ghosh - University of Denver

This article explores the use of nighttime satellite imagery for mapping urban and peri-urban areas of Australia. A population-weighted measure of urban sprawl is used to characterize relative levels of sprawl for Australia’s urban areas. In addition, the expansive areas of low light surrounding most major metropolitan areas are used to map the urban–bush interface of exurban land use. Our findings suggest that 82 percent of the Australian population lives in urban areas, 15 percent live in peri-urban or exurban areas, and 3 percent live in rural areas. This represents a significantly more concentrated human settlement pattern than presently exists in the United States.

Urban Decentralization Processes

Methods

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

Nighttime satellite imagery has been used to map urban and an exurban population in the United States and this article demonstrates that the same methods are reasonable for mapping similar urban and exurban environments in Australia. Comparing these results with prior studies of U.S. cities shows that Australia is significantly more urban than the United States and Australia’s urban areas do not sprawl in either an urban or peri-urban way relative to those in the United States. Within Australia, Sydney sprawls the least and Brisbane sprawls the most. Perth sprawls a bit, but Melbourne and Adelaide do not. Comparing the peri-urban populations and areal extent of these five big cities is problematic due to the differing degree of conurbation they have with nearby large cities (e.g., Sydney with Newcastle and Woo- longong; Brisbane with the Gold Coast; Perth with Freemantle and Mandurah; Melbourne with Geelong; and Adelaide with Mt. Barker). Future demographic, economic, social, political, and ethical decisions and nondecisions will determine whether Australia will move toward or away from the urban and exurban sprawl that presently exists in the United States.

Literature Cited

in:

Sutton, Paul C., Goetz, Andrew R., Fildes, Stephen, Forster, Clive and Ghosh, Tilottama(2010) 'Darkness on the Edge of Town: Mapping Urban and Peri-Urban Australia Using Nighttime Satellite Imagery', The Professional Geographer, 62: 1, 119 — 133, First published on: 11 December 2009 (iFirst)

link para o texto integral:

http://urizen-geography.nsm.du.edu/~psutton/AAA_Sutton_WebPage/Sutton/Publications/Sut_Pub_9.pdf

28 de agosto de 2012

Que futuro para antigas fábricas abandonadas?

Conceição Melo

Jornal "Público"

20-08-2012

A Fábrica de Fiação e Tecidos de Santo Thyrso foi uma das mais emblemáticas fábricas do Vale do Ave, coração da indústria têxtil e do vestuário português, tendo empregado nos seus tempos áureos mais de mil trabalhadores. Por este motivo, existe ainda hoje uma forte ligação sentimental da população para com este espaço. Pioneira no desenvolvimento industrial da região, esta fábrica não resistiu às mudanças estruturais do sistema económico e produtivo que, nos anos oitenta, colocaram desprotegidamente as nossas indústrias no mercado global. Fechou as suas portas em 1990.

Ultrapassando as suas competências estritas, a câmara municipal iniciou um longo processo para a aquisição deste património, aceitando o desígnio de manter viva a memória e a identidade coletivas.

A requalificação da Fábrica de Santo Thyrso enquadra-se numa intervenção de regeneração urbana mais alargada que visa tornar as frentes ribeirinhas do rio Ave um espaço de sociabilidade e de fruição para todos os habitantes, turistas e visitantes de Santo Tirso, ao qual se associa a promoção de atividades culturais e económicas, criativas, urbanas, inovadoras e diferenciadoras. Este processo suportado por um Plano Municipal de Ordenamento do Território, o Plano de Urbanização das Margens do Ave, fundamentou uma candidatura bem-sucedida ao Polis XXI, Parcerias para a Regeneração Urbana, que possibilitou o acesso a financiamento comunitário e viabilizou a recuperação de parte significativa deste património.

São razões de ordem patrimonial e identitária e de ordem económica e social as que norteiam todo este projeto.

Memória e identidade são valores subjetivos. Neste caso, encontram-se associadas a um lugar, um espaço edificado e fabricado, que esteve ligado à história pessoal de muitos dos habitantes de Santo Tirso e à história económica do município e da região. A preservação desta memória coletiva não se faz sem a sua continuidade na contemporaneidade. E a dificuldade reside aí. Como preservar a memória e a identidade, fatores que contribuem para o bem-estar e a coesão social, adotando e adaptando o espaço a novos usos? Como conseguir que a população local se aproprie e faça seu este novo projeto?

A apropriação implica a identificação com o objetivo e com o lugar socialmente produzido em continuidade, integrando o passado no novo uso e garantindo deste modo a sua viabilidade futura: ao significado cultural e histórico, há que acrescentar os novos significados trazidos pelas novas funções; à preservação da memória patrimonial, conseguida pela leitura interpretativa do edifício e da sua original função, haverá que adicionar a gerada pelas atividades que aqui se vão sedimentar.

Mais do que a requalificação física do espaço pretende-se um verdadeiro projeto de regeneração urbana que obrigatoriamente pressupõe uma perspetiva evolutiva e vivencial do património. Não interessa ao município, não interessa à cidade, guardar estaticamente a memória do lugar, interessa recompô-la com novas vivências, abertas à comunidade local.

Este é o principal desafio do projeto: abri-lo ao exterior, divulgando-o externamente, estabelecendo parcerias e trazendo experiências e projetos para serem desenvolvidos no espaço da Fábrica de Santo Thyrso e, ao mesmo tempo, incorporar o saber fazer dos antigos operários têxteis, os métodos produtivos tradicionais da cultura local, fazendo-os coincidir na contemporaneidade.

É neste espaço e neste contexto, de elevado simbolismo e de projetado dinamismo, que está a ser concretizado sob o conceito de Quarteirão Cultural o projeto "Fábrica de Santo Thyrso", projeto este que configura, em nosso entender, um bom exemplo de uma operação de regeneração urbana. Oxalá se concretize.

in: "CIDADES PELA RETOMA & TRANSIÇÂO"

texto original:

http://jornal.publico.pt/noticia/20-08-2012/que-futuro-para-antigas-fabricas-abandonadas-25096514.htm

enviado por:

Maria Teresa Goulão

Jornal "Público"

20-08-2012

A Fábrica de Fiação e Tecidos de Santo Thyrso foi uma das mais emblemáticas fábricas do Vale do Ave, coração da indústria têxtil e do vestuário português, tendo empregado nos seus tempos áureos mais de mil trabalhadores. Por este motivo, existe ainda hoje uma forte ligação sentimental da população para com este espaço. Pioneira no desenvolvimento industrial da região, esta fábrica não resistiu às mudanças estruturais do sistema económico e produtivo que, nos anos oitenta, colocaram desprotegidamente as nossas indústrias no mercado global. Fechou as suas portas em 1990.

Ultrapassando as suas competências estritas, a câmara municipal iniciou um longo processo para a aquisição deste património, aceitando o desígnio de manter viva a memória e a identidade coletivas.

A requalificação da Fábrica de Santo Thyrso enquadra-se numa intervenção de regeneração urbana mais alargada que visa tornar as frentes ribeirinhas do rio Ave um espaço de sociabilidade e de fruição para todos os habitantes, turistas e visitantes de Santo Tirso, ao qual se associa a promoção de atividades culturais e económicas, criativas, urbanas, inovadoras e diferenciadoras. Este processo suportado por um Plano Municipal de Ordenamento do Território, o Plano de Urbanização das Margens do Ave, fundamentou uma candidatura bem-sucedida ao Polis XXI, Parcerias para a Regeneração Urbana, que possibilitou o acesso a financiamento comunitário e viabilizou a recuperação de parte significativa deste património.

São razões de ordem patrimonial e identitária e de ordem económica e social as que norteiam todo este projeto.

Memória e identidade são valores subjetivos. Neste caso, encontram-se associadas a um lugar, um espaço edificado e fabricado, que esteve ligado à história pessoal de muitos dos habitantes de Santo Tirso e à história económica do município e da região. A preservação desta memória coletiva não se faz sem a sua continuidade na contemporaneidade. E a dificuldade reside aí. Como preservar a memória e a identidade, fatores que contribuem para o bem-estar e a coesão social, adotando e adaptando o espaço a novos usos? Como conseguir que a população local se aproprie e faça seu este novo projeto?

A apropriação implica a identificação com o objetivo e com o lugar socialmente produzido em continuidade, integrando o passado no novo uso e garantindo deste modo a sua viabilidade futura: ao significado cultural e histórico, há que acrescentar os novos significados trazidos pelas novas funções; à preservação da memória patrimonial, conseguida pela leitura interpretativa do edifício e da sua original função, haverá que adicionar a gerada pelas atividades que aqui se vão sedimentar.

Mais do que a requalificação física do espaço pretende-se um verdadeiro projeto de regeneração urbana que obrigatoriamente pressupõe uma perspetiva evolutiva e vivencial do património. Não interessa ao município, não interessa à cidade, guardar estaticamente a memória do lugar, interessa recompô-la com novas vivências, abertas à comunidade local.

Este é o principal desafio do projeto: abri-lo ao exterior, divulgando-o externamente, estabelecendo parcerias e trazendo experiências e projetos para serem desenvolvidos no espaço da Fábrica de Santo Thyrso e, ao mesmo tempo, incorporar o saber fazer dos antigos operários têxteis, os métodos produtivos tradicionais da cultura local, fazendo-os coincidir na contemporaneidade.

É neste espaço e neste contexto, de elevado simbolismo e de projetado dinamismo, que está a ser concretizado sob o conceito de Quarteirão Cultural o projeto "Fábrica de Santo Thyrso", projeto este que configura, em nosso entender, um bom exemplo de uma operação de regeneração urbana. Oxalá se concretize.

in: "CIDADES PELA RETOMA & TRANSIÇÂO"

texto original:

http://jornal.publico.pt/noticia/20-08-2012/que-futuro-para-antigas-fabricas-abandonadas-25096514.htm

enviado por:

Maria Teresa Goulão

27 de agosto de 2012

ÍNDIA - "Financing the Development of Small and Medium Cities"

Financing the Development of Small and Medium Cities

Anand Sahasranaman

Urbanisation in India is currently marked by two fundamental trends: lopsided migration to the larger cities and unbalanced regional economic development. In this context, this paper makes a case for the concerted development of small and medium cities as the key focus in the strategy to ensure sustainable urbanisation in India. As cities plan for the long term, among the most critical components they need are the availability of land and the provision of infrastructure and services for a growing population. This paper suggests the need for land banks and land readjustment mechanisms, and assesses the efficacy of current mechanisms for infrastructure provision in small and medium cities. There is also a rationale and need for the creation of new cities, either on the peripheries of large cities or around industrial clusters, with private participation and financing.

The urban population of India is concentrated in large cities. More than 60% of the urban population lived in Class I cities as of 2001. Chattopadhyay (2008) points out that the rate of population growth in these Class I cities has also been consistently increasing over the past five decades, from 45% in 1961-71 to 62% in 1991-2001. This has been accompanied by a decrease in population growth in smaller urban centres. This trend of migration towards the larger cities is due, in large part, to the economic prominence of these cities. These cities are the engines of economic growth, but are plagued by severe challenges to their civic infrastructure and service delivery capabilities. For this reason, they are deemed to be at the forefront of the urban challenge today.

India is rapidly urbanising and the rate of urbanisation is expected to climb steeply over the next few decades. McKinsey Global Institute (2010) predicts an urban popula- tion of 590 million by 2030, as compared to 340 million in 2008. For India to be more inclusive, it is imperative that both economic growth and urban population be more equitably distributed. Therefore, any meaningful long-term vision for India would be incomplete without planning for the cities of tomorrow.

Where Are the Cities of Tomorrow?

Why Small and Medium Cities?

An Assessment of the Current Scenario

A Comprehensive Approach to Development

Financial Incentives

Financing Land and Infrastructure

- Land Banks and How to Finance Them

- Innovative Financing of Land and Infrastructure through Land Pooling

- The Centrality of Grant Funding for New Infrastructure Creation

- Debt Financing for New Infrastructure Creation

Development of New Cities

- Nodes at Over-Congested City Peripheries

Development and Financing of Industrial Cities

Conclusions

Urbanisation in India is currently marked by two fundamental trends – lopsided migration to the larger cities and unbalanced regional economic development. Both these trends need to be reversed.

This paper makes a case for the concerted development of small and medium cities as key to the strategy for ensuring sustainable urbanisation in India. The development of these cities can disperse rural migration and ensure more balanced regional development. However, smaller cities are hobbled by problems of poor economic prospects and low levels of infrastructure provision; government programmes aimed at these cities have failed to achieve any meaningful change in this scenario. There needs to be a new approach to the planning of these cities.

Theory suggests that smaller cities are fundamentally linked with their rural hinterlands and these rural-urban linkages encompass human, financial and market connections. Any planning exercise for these cities should incorporate their surrounding rural areas and therefore, a regional planning framework that includes economic development and infrastructure planning for an entire district may be the way forward. Constitutionally-mandated DPCs may be the best vehicle to undertake this planning exercise. Although the performance of DPCs on the ground so far leaves much to be desired, improved performance can be incentivised by linking conditional grants from the centre to state governments on the composition and operationalisation of DPCs in the state.

The next important question relates to the financing of infrastructure and service delivery for these small and medium cities. As cities plan for the long term, one of the most critical components they need to plan for is the availability of land. Small cities should look to create the land banks that they will need for future development by acquiring these lands upfront. These land banks can be financed with the help of a derivative product provided by the central government that guarantees a minimum increase in land values (say 1%). Small cities can use this guarantee to borrow from banks that would otherwise be unwilling to lend to them and thus finance their land banks.

However, land acquisition can be a complex, time-consuming process and wherever feasible, mechanisms such as Land Re- adjustment and Pooling (LRP) can be used to make lands avail- able for development without needing them to be acquired. LRP is a self-financing mechanism that allows for landowners to work as partners with local government and enables comprehensive planning of land and infrastructure provision. LRP should be legislated in the town planning acts of all Indian states.

The financing of new infrastructure provision in small and medium cities will be dependent on grant funding for the short term. The UIDSSMT programme should be given high priority and cities should be encouraged to prepare project proposals for funding. The UIDSSMT financing mechanism can be modified with a new feature, making available a portion of UIDSSMT funds to be used as guarantee funds for pooled bond issues. This can ensure that UIDSSMT funds are leveraged to a greater extent than they are currently and reach a larger number of cities.

There also needs to be a concerted push to revive the moribund pooled financing scheme that allows multiple small cities to pool together their infrastructure projects and access the capital markets with bond issues to raise financing. Despite a few successful pooled bond issues, there has been a distinct lack of activity in this market. This can be attributed to a guideline that requires that tax-free pooled bonds be issued at 8% or less. This stringent requirement makes new bond issues economically unviable. It must be revised so that the interest rate cap is a spread over a benchmark rate, such as the govern- ment securities rate.

The development of small and medium cities is essential to sustainable urbanisation, and it can be augmented by the development of new cities. New city development can take the form of development of nodes near large existing cities in order to ease the population pressure on the latter. These nodes are designed to decongest the larger cities. One way to finance the development of such nodal cities is through the issue of long-term local government bonds backed by partial central government guarantees.

New cities can also be developed around large industries and industrial clusters. Since these industries are private ven- tures, there is tremendous scope for involving the private sec- tor in planning the development of these cities and getting them to substantially participate in financing the creation of infrastructure, even as equity partners. Such cities can also experiment with other innovative service delivery and financ- ing mechanisms that could have tremendous relevance for the country at large.

Urbanisation in India is gathering momentum and in order to be able to plan for a sustainable urban future, immediate attention needs to be paid to the small and medium cities of the country. It is only through the focused development of these cities as the cities of tomorrow can India develop a meaningful long-term urbanisation strategy.

Link para o artigo integral:

http://www.ifmr.co.in/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Financing_the_Development_of_Small_and_Medium_Cities.pdf

In:

IFMR Trust

Anand Sahasranaman

Urbanisation in India is currently marked by two fundamental trends: lopsided migration to the larger cities and unbalanced regional economic development. In this context, this paper makes a case for the concerted development of small and medium cities as the key focus in the strategy to ensure sustainable urbanisation in India. As cities plan for the long term, among the most critical components they need are the availability of land and the provision of infrastructure and services for a growing population. This paper suggests the need for land banks and land readjustment mechanisms, and assesses the efficacy of current mechanisms for infrastructure provision in small and medium cities. There is also a rationale and need for the creation of new cities, either on the peripheries of large cities or around industrial clusters, with private participation and financing.

The urban population of India is concentrated in large cities. More than 60% of the urban population lived in Class I cities as of 2001. Chattopadhyay (2008) points out that the rate of population growth in these Class I cities has also been consistently increasing over the past five decades, from 45% in 1961-71 to 62% in 1991-2001. This has been accompanied by a decrease in population growth in smaller urban centres. This trend of migration towards the larger cities is due, in large part, to the economic prominence of these cities. These cities are the engines of economic growth, but are plagued by severe challenges to their civic infrastructure and service delivery capabilities. For this reason, they are deemed to be at the forefront of the urban challenge today.

India is rapidly urbanising and the rate of urbanisation is expected to climb steeply over the next few decades. McKinsey Global Institute (2010) predicts an urban popula- tion of 590 million by 2030, as compared to 340 million in 2008. For India to be more inclusive, it is imperative that both economic growth and urban population be more equitably distributed. Therefore, any meaningful long-term vision for India would be incomplete without planning for the cities of tomorrow.

Where Are the Cities of Tomorrow?

Why Small and Medium Cities?

An Assessment of the Current Scenario

A Comprehensive Approach to Development

Financial Incentives

Financing Land and Infrastructure

- Land Banks and How to Finance Them

- Innovative Financing of Land and Infrastructure through Land Pooling

- The Centrality of Grant Funding for New Infrastructure Creation

- Debt Financing for New Infrastructure Creation

Development of New Cities

- Nodes at Over-Congested City Peripheries

Development and Financing of Industrial Cities

Conclusions

Urbanisation in India is currently marked by two fundamental trends – lopsided migration to the larger cities and unbalanced regional economic development. Both these trends need to be reversed.

This paper makes a case for the concerted development of small and medium cities as key to the strategy for ensuring sustainable urbanisation in India. The development of these cities can disperse rural migration and ensure more balanced regional development. However, smaller cities are hobbled by problems of poor economic prospects and low levels of infrastructure provision; government programmes aimed at these cities have failed to achieve any meaningful change in this scenario. There needs to be a new approach to the planning of these cities.

Theory suggests that smaller cities are fundamentally linked with their rural hinterlands and these rural-urban linkages encompass human, financial and market connections. Any planning exercise for these cities should incorporate their surrounding rural areas and therefore, a regional planning framework that includes economic development and infrastructure planning for an entire district may be the way forward. Constitutionally-mandated DPCs may be the best vehicle to undertake this planning exercise. Although the performance of DPCs on the ground so far leaves much to be desired, improved performance can be incentivised by linking conditional grants from the centre to state governments on the composition and operationalisation of DPCs in the state.

The next important question relates to the financing of infrastructure and service delivery for these small and medium cities. As cities plan for the long term, one of the most critical components they need to plan for is the availability of land. Small cities should look to create the land banks that they will need for future development by acquiring these lands upfront. These land banks can be financed with the help of a derivative product provided by the central government that guarantees a minimum increase in land values (say 1%). Small cities can use this guarantee to borrow from banks that would otherwise be unwilling to lend to them and thus finance their land banks.

However, land acquisition can be a complex, time-consuming process and wherever feasible, mechanisms such as Land Re- adjustment and Pooling (LRP) can be used to make lands avail- able for development without needing them to be acquired. LRP is a self-financing mechanism that allows for landowners to work as partners with local government and enables comprehensive planning of land and infrastructure provision. LRP should be legislated in the town planning acts of all Indian states.

The financing of new infrastructure provision in small and medium cities will be dependent on grant funding for the short term. The UIDSSMT programme should be given high priority and cities should be encouraged to prepare project proposals for funding. The UIDSSMT financing mechanism can be modified with a new feature, making available a portion of UIDSSMT funds to be used as guarantee funds for pooled bond issues. This can ensure that UIDSSMT funds are leveraged to a greater extent than they are currently and reach a larger number of cities.

There also needs to be a concerted push to revive the moribund pooled financing scheme that allows multiple small cities to pool together their infrastructure projects and access the capital markets with bond issues to raise financing. Despite a few successful pooled bond issues, there has been a distinct lack of activity in this market. This can be attributed to a guideline that requires that tax-free pooled bonds be issued at 8% or less. This stringent requirement makes new bond issues economically unviable. It must be revised so that the interest rate cap is a spread over a benchmark rate, such as the govern- ment securities rate.

The development of small and medium cities is essential to sustainable urbanisation, and it can be augmented by the development of new cities. New city development can take the form of development of nodes near large existing cities in order to ease the population pressure on the latter. These nodes are designed to decongest the larger cities. One way to finance the development of such nodal cities is through the issue of long-term local government bonds backed by partial central government guarantees.

New cities can also be developed around large industries and industrial clusters. Since these industries are private ven- tures, there is tremendous scope for involving the private sec- tor in planning the development of these cities and getting them to substantially participate in financing the creation of infrastructure, even as equity partners. Such cities can also experiment with other innovative service delivery and financ- ing mechanisms that could have tremendous relevance for the country at large.

Urbanisation in India is gathering momentum and in order to be able to plan for a sustainable urban future, immediate attention needs to be paid to the small and medium cities of the country. It is only through the focused development of these cities as the cities of tomorrow can India develop a meaningful long-term urbanisation strategy.

Link para o artigo integral:

http://www.ifmr.co.in/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Financing_the_Development_of_Small_and_Medium_Cities.pdf

In:

IFMR Trust

26 de agosto de 2012

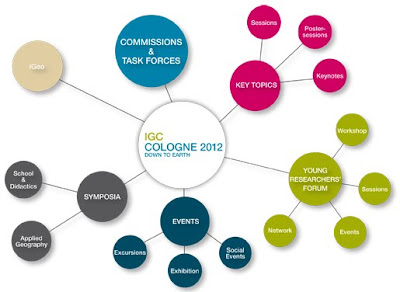

32nd International Geographical Congress

IGC Cologne 2012 - DOWN TO EARTH

Quando: 26 - 30 August 2012

Onde: Cologne

The IGC is the quadrennial meeting of the International Geographical Union (IGU). Besides the traditional meetings of the IGC Commissions the 32nd International Geographical Congress in Cologne focuses scientific attention on the core themes of humanity.

Geographers bring the wide-ranging perspectives and methodology of their subject to bear on four major thematic complexes and contribute to the solution of urgent scientific and socio-political issues – bringing research down to earth:

- Global Change and Globalisation

- Society and Environment

- Risks and Conflicts

- Urbanisation and Demographic Change

Mais informação:

Quando: 26 - 30 August 2012

Onde: Cologne

The IGC is the quadrennial meeting of the International Geographical Union (IGU). Besides the traditional meetings of the IGC Commissions the 32nd International Geographical Congress in Cologne focuses scientific attention on the core themes of humanity.

Geographers bring the wide-ranging perspectives and methodology of their subject to bear on four major thematic complexes and contribute to the solution of urgent scientific and socio-political issues – bringing research down to earth:

- Global Change and Globalisation

- Society and Environment

- Risks and Conflicts

- Urbanisation and Demographic Change

Mais informação:

Circuler. Quand nos mouvements façonnent les villes

Exposition conçue et réalisée par la Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine / Ifa

Quando:

04 avril 2012 - 26 août 2012

Onde:

Paris - Place du Trocadéro - Palais de Chaillot

Cité de l'architecture & du patrimoine - Galerie haute des expositions temporaires

Aller ou demeurer, partir ou rester, la vie d’un homme est faite de moments où il circule et de moments où il s’arrête.

L’espace des villes, l’espace entre les villes, l’architecture accompagnent ce mouvement permanent de l’humanité. L’exposition, dont le commissariat est assuré par l’architecte et ingénieur Jean-Marie Duthilleul, permet au visiteur de suivre à travers le temps, des origines au futur proche, l’évolution des conceptions urbaines, des espaces urbains, des bâtiments générés par la circulation des hommes à travers les territoires.

Le concept de « circulation » est également redéfini, puisqu’aujourd’hui, la circulation des hommes évolue de plus en plus vers une circulation virtuelle. Rues et places, routes, autoroutes ou voies ferrées, ports, caravansérails, gares et aérogares, villes compactes, villes éclatées, autant de concepts qui jalonnent l’histoire des territoires et qui trouvent leur origine dans le désir de chacun de circuler pour aller à la rencontre de l’autre et de sa richesse. Un parcours ludique et sensoriel, mis en scène comme un décor de théâtre permet au visiteur d’effectuer en 9 séquences un parcours chronologique depuis les premières villes de l’humanité, jusqu’aux villes de demain et de comprendre comment la mobilité façonne l’espace.

Mais informação:

http://www.citechaillot.fr/fr/expositions/expositions_temporaires/24415-circuler_quand_nos_mouvements_faconnent_les_villes.html

Quando:

04 avril 2012 - 26 août 2012

Onde:

Paris - Place du Trocadéro - Palais de Chaillot

Cité de l'architecture & du patrimoine - Galerie haute des expositions temporaires

Aller ou demeurer, partir ou rester, la vie d’un homme est faite de moments où il circule et de moments où il s’arrête.

L’espace des villes, l’espace entre les villes, l’architecture accompagnent ce mouvement permanent de l’humanité. L’exposition, dont le commissariat est assuré par l’architecte et ingénieur Jean-Marie Duthilleul, permet au visiteur de suivre à travers le temps, des origines au futur proche, l’évolution des conceptions urbaines, des espaces urbains, des bâtiments générés par la circulation des hommes à travers les territoires.

Le concept de « circulation » est également redéfini, puisqu’aujourd’hui, la circulation des hommes évolue de plus en plus vers une circulation virtuelle. Rues et places, routes, autoroutes ou voies ferrées, ports, caravansérails, gares et aérogares, villes compactes, villes éclatées, autant de concepts qui jalonnent l’histoire des territoires et qui trouvent leur origine dans le désir de chacun de circuler pour aller à la rencontre de l’autre et de sa richesse. Un parcours ludique et sensoriel, mis en scène comme un décor de théâtre permet au visiteur d’effectuer en 9 séquences un parcours chronologique depuis les premières villes de l’humanité, jusqu’aux villes de demain et de comprendre comment la mobilité façonne l’espace.

Mais informação:

http://www.citechaillot.fr/fr/expositions/expositions_temporaires/24415-circuler_quand_nos_mouvements_faconnent_les_villes.html

25 de agosto de 2012

Curso de verão "Future Cities - dream it, build it, live it"

Mais de duas dezenas de estudantes europeus vão participar no curso de verão sobre Cidades do Futuro e Sustentabilidade, que se realiza de 25 de agosto a 6 de setembro, na Universidade de Aveiro.

O curso intitulado "Future Cities - dream it, build it, live it" é promovido pelo grupo BEST Aveiro e inclui diversas palestras e tertúlias nas áreas de energias renováveis, ambiente, planeamento urbanístico, novos materiais, telecomunicações, construção e mobilidade.

Está ainda a ser planeado um "Company Day", proporcionando uma ligação direta entre a indústria e estudantes e aberto a toda a comunidade académica, em que várias empresas terão a oportunidade de apresentar as mais recentes tecnologias nas diversas áreas do curso.

Este é o segundo curso internacional promovido pelo BEST Aveiro, que está inserido no Board of European Students of Technology, uma organização europeia de estudantes de Ciência, Engenharia e Tecnologia.

link:

http://bestaveiro.web.ua.pt/sc2012/

in:

Cidades pela Retoma

enviado por:

Maria Teresa Goulão

O curso intitulado "Future Cities - dream it, build it, live it" é promovido pelo grupo BEST Aveiro e inclui diversas palestras e tertúlias nas áreas de energias renováveis, ambiente, planeamento urbanístico, novos materiais, telecomunicações, construção e mobilidade.

Está ainda a ser planeado um "Company Day", proporcionando uma ligação direta entre a indústria e estudantes e aberto a toda a comunidade académica, em que várias empresas terão a oportunidade de apresentar as mais recentes tecnologias nas diversas áreas do curso.

Este é o segundo curso internacional promovido pelo BEST Aveiro, que está inserido no Board of European Students of Technology, uma organização europeia de estudantes de Ciência, Engenharia e Tecnologia.

link:

http://bestaveiro.web.ua.pt/sc2012/

in:

Cidades pela Retoma

enviado por:

Maria Teresa Goulão

24 de agosto de 2012

AGROPOLITANA: COUNTRYSIDE AND URBAN SPRAWL IN THE VENETO REGION (ITALY)

Viviana Ferrario

Abstract

In the Veneto central plane, historically shaped by agriculture, the countryside is being taken over by a particular form of urban sprawl, called città diffusa (dispersed city), where cities, villages, single houses and industries live alongside agriculture. This phenomenon is generally analyzed mainly as a typical urban/rural conflict, and the sprawl gets criticized as a countryside destroyer.

By observing some paradoxical situations in the città diffusa in Veneto, the contrary is apparent – urban sprawl seems to have been rather a conservation factor for the ecological and cultural richness of the agricultural space. Agricultural space itself plays an important multifunctional role in this territory. If seen from this point of view, dispersed urbanization in the Veneto region can be seen as a sort of prototype of a new contemporary form - neither urban nor rural – of cultural landscape, where farming spaces can have a public role strictly linked to the urban population's needs.

Can this character be preserved through the metropolization process now envisaged by regional policy and planning, and already happening? Can the “Agropolitana” concept introduced by the new Regional Spatial Plan help to imagine and obtain a resilient metropolis, while maintaining a strong agricultural layer inside it?

7. Agropolitana: an idea for the future?

Since their beginnings, urbanization processes have been interpreted not only as countryside destroyers, but also as a potential form of cooperation of rural and urban inhabitants, resulting in the disappearance of the town/country dichotomy (Juillard 1973). In the past, this long-lasting idea inspired several famous urban theories - from Howard’s garden-city (1902), to Schwartz’s stadtlandschaft (1946) - and fascinating predictions - from Wells’ diffusion of cities (1902) to Sorokin and Zimmermann’s rurbanisation (1929).

The present debate will stress the need for a new relationship between cities and open territory, giving agriculture a new centrality in our territories’ future. If we should “delegate to nature” many of our cities' needs (Sassen, 2009), urbanization should become “awake”, learning not by industry processes, as it did in the 20th century, but by agriculture, capable of gently manipulating nature (Branzi, 2005). The presence of agricultural space in urban structures is extremely important since it may improve their resilience (Garnett 1999, Mougeot 2005, Urban Agriculture 2009).

Could the Veneto città diffusa be considered to be a sort of prototype for this integration? This model is maybe not the best possible one, but has some positive aspects, despite the land consumption issue. Land consumption must be considered not only in a quantitative way, but also as a problem of territorial form, having a better or worse performance in the face of new challenges, the first being sustainability.

Agriculture space, in fact, has the capacity to host contemporarily different functions like food production, energy production, environmental values, leisure and other social services. Its permeability performs well in cases of heavy rain and, under certain conditions, it can be used as an emergency flooding area. The chains of production (for example the corn cultivation - cattle breeding - beef to export chain) can be shortened to increase sustainability. When needed, food for inhabitants can be produced by their own territory. We should also acknowledge the role of small scale and part-time agriculture in landscape and environment conservation.

In this sense, the presence of agricultural space inside the upcoming Veneto metropolis must be considered as a warranty for a sustainable future. The agropolitana concept, however, must be explored in order to better integrate agricultural space into the design of urban development. Devising a concrete project for this space – a project for its multifunctionality – is what still needs to be done.

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.ff.uni-mb.si/zalozba-in-knjigarna/ponudba/zbirke-in-revije/revija-za-geografijo/clanki/stevilka-4-2-2009/042-11_ferrario.pdf

in:

Revija za geografijo - Journal for Geography, 4-2, 2009, 129-142

Abstract

In the Veneto central plane, historically shaped by agriculture, the countryside is being taken over by a particular form of urban sprawl, called città diffusa (dispersed city), where cities, villages, single houses and industries live alongside agriculture. This phenomenon is generally analyzed mainly as a typical urban/rural conflict, and the sprawl gets criticized as a countryside destroyer.

By observing some paradoxical situations in the città diffusa in Veneto, the contrary is apparent – urban sprawl seems to have been rather a conservation factor for the ecological and cultural richness of the agricultural space. Agricultural space itself plays an important multifunctional role in this territory. If seen from this point of view, dispersed urbanization in the Veneto region can be seen as a sort of prototype of a new contemporary form - neither urban nor rural – of cultural landscape, where farming spaces can have a public role strictly linked to the urban population's needs.

Can this character be preserved through the metropolization process now envisaged by regional policy and planning, and already happening? Can the “Agropolitana” concept introduced by the new Regional Spatial Plan help to imagine and obtain a resilient metropolis, while maintaining a strong agricultural layer inside it?

7. Agropolitana: an idea for the future?

Since their beginnings, urbanization processes have been interpreted not only as countryside destroyers, but also as a potential form of cooperation of rural and urban inhabitants, resulting in the disappearance of the town/country dichotomy (Juillard 1973). In the past, this long-lasting idea inspired several famous urban theories - from Howard’s garden-city (1902), to Schwartz’s stadtlandschaft (1946) - and fascinating predictions - from Wells’ diffusion of cities (1902) to Sorokin and Zimmermann’s rurbanisation (1929).

The present debate will stress the need for a new relationship between cities and open territory, giving agriculture a new centrality in our territories’ future. If we should “delegate to nature” many of our cities' needs (Sassen, 2009), urbanization should become “awake”, learning not by industry processes, as it did in the 20th century, but by agriculture, capable of gently manipulating nature (Branzi, 2005). The presence of agricultural space in urban structures is extremely important since it may improve their resilience (Garnett 1999, Mougeot 2005, Urban Agriculture 2009).

Could the Veneto città diffusa be considered to be a sort of prototype for this integration? This model is maybe not the best possible one, but has some positive aspects, despite the land consumption issue. Land consumption must be considered not only in a quantitative way, but also as a problem of territorial form, having a better or worse performance in the face of new challenges, the first being sustainability.

Agriculture space, in fact, has the capacity to host contemporarily different functions like food production, energy production, environmental values, leisure and other social services. Its permeability performs well in cases of heavy rain and, under certain conditions, it can be used as an emergency flooding area. The chains of production (for example the corn cultivation - cattle breeding - beef to export chain) can be shortened to increase sustainability. When needed, food for inhabitants can be produced by their own territory. We should also acknowledge the role of small scale and part-time agriculture in landscape and environment conservation.

In this sense, the presence of agricultural space inside the upcoming Veneto metropolis must be considered as a warranty for a sustainable future. The agropolitana concept, however, must be explored in order to better integrate agricultural space into the design of urban development. Devising a concrete project for this space – a project for its multifunctionality – is what still needs to be done.

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.ff.uni-mb.si/zalozba-in-knjigarna/ponudba/zbirke-in-revije/revija-za-geografijo/clanki/stevilka-4-2-2009/042-11_ferrario.pdf

in:

Revija za geografijo - Journal for Geography, 4-2, 2009, 129-142

23 de agosto de 2012

Urban sprawl in Europe – identifying the challenge

Stefan FINA, Stefan SIEDENTOP

(reviewed paper)

1 ABSTRACT

In Europe, research on urban sprawl is largely limited to case studies of selected metropolitan areas in a national context. In addition, the literature to date does not present comprehensive empirical evidence as to what exactly constitutes urban sprawl. Accordingly, the European Environment Agency describes urban sprawl as the “The ignored challenge” in the subtitle to its 2006 report on urban sprawl (European Environment Agency, 2006). This article aims to deliver a contribution for identifying the “challenge”: it provides a consistent overview for the area-wide distribution and characterisation of urban sprawl in Europe, based on CORINE land cover data and a set of GIS-based indicators. The indicators are built upon a framework that allows for the differentiation of distinct types of urban sprawl, including measures that compare land cover change over time. The results are presented as continuous maps of Europe for different indicators of urban sprawl, and interpreted in the context of their characteristics and distribution.

2 INTRODUCTION

3 APPROACH AND RELEVANCE

4 DESCRIPTION OF INDICATORS

4.1 Data

4.2 Indicators

4.3 Methodology

5 RESULTS

Figure 7 summarises the two impact dimensions we have discussed in this paper. Each of the indicators contributed with its most urban sprawl- or growth-like features towards the classification in this map. According to this, surface sprawl / growth is particularly evident in Spain, Greece, and The Netherlands. Pattern sprawl is significant in the Benelux countries, in some areas of England, Germany, France, Poland, Austria, and Hungary. Overall, we identify these areas to be risk areas for urban sprawl for future research to focus upon.

6 CONCLUSION

Our maps presented in chapter 5 display areas with an “above average risk” of adverse land use related impacts. Areas with a high share of urban land experience significant hydrologic and mesoclimatic changes (excessive urban runoff, heat island effects) due to the spatial concentration of impervious surfaces. These areas are also characterized by a scarcity of valuable open space – both in absolute terms and per capita – and a quantitative loss of prime agricultural land and wildlife habitats. Regions or subregions with an irregular, dispersed and discontinuous urban form may be affected by a reduced efficiency of public transport systems and urban infrastructures (roads, water supply, sewer systems) and a higher per capita energy consumption (as an effect of larger travel distances). Furhtermore, areas with significant “pattern sprawl” as indicated in figure 7 witness higher risks of threats to endangered species due to landscape fragmentation and the high level of habitat disturbance.

At the same time, our analysis depicts “success stories” of implementing sustainable land use policies across the European Union. Examples refer to the relatively compact urban form and growth in parts of The Netherlands and the United Kingdom notwithstanding a high level of population density and urbanisation in both countries. Figure 3 gives evidence of a significant South-North divide in the use of ecologically sensitive areas for urban purposes. More effective or established landscape planning schemes and higher standards of environmental impact assessement in Northern Europe may explain this observation.

Furthermore, the relatively low degree of urbanisation in large parts of Scandinavia, Spain, Greece, Scotland, Ireland and southern Italy must be seen as an important ecological resource to be carefully managed in the future.

The measurement concept presented in this paper creates a methodological framework for evaluating the success of future land use policies and landscape protections programs. We deliberately avoided developing a composite sprawl index that aggregates the impact dimensions discussed above. The problem we see is that different sprawl indicators tend to outweigh each other in the process of aggregation. Therefore we recommend the use of dimension related sprawl types attributed with a specific profile of environmental and economic problems (see figure 7). Taking this into account, type-specific anti-sprawl strategies and instruments could be implemented.

7 REFERENCES

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/ireus/publikationen/CORP2008_34.pdf

(reviewed paper)

1 ABSTRACT

In Europe, research on urban sprawl is largely limited to case studies of selected metropolitan areas in a national context. In addition, the literature to date does not present comprehensive empirical evidence as to what exactly constitutes urban sprawl. Accordingly, the European Environment Agency describes urban sprawl as the “The ignored challenge” in the subtitle to its 2006 report on urban sprawl (European Environment Agency, 2006). This article aims to deliver a contribution for identifying the “challenge”: it provides a consistent overview for the area-wide distribution and characterisation of urban sprawl in Europe, based on CORINE land cover data and a set of GIS-based indicators. The indicators are built upon a framework that allows for the differentiation of distinct types of urban sprawl, including measures that compare land cover change over time. The results are presented as continuous maps of Europe for different indicators of urban sprawl, and interpreted in the context of their characteristics and distribution.

2 INTRODUCTION

3 APPROACH AND RELEVANCE

4 DESCRIPTION OF INDICATORS

4.1 Data

4.2 Indicators

4.3 Methodology

5 RESULTS

Figure 7 summarises the two impact dimensions we have discussed in this paper. Each of the indicators contributed with its most urban sprawl- or growth-like features towards the classification in this map. According to this, surface sprawl / growth is particularly evident in Spain, Greece, and The Netherlands. Pattern sprawl is significant in the Benelux countries, in some areas of England, Germany, France, Poland, Austria, and Hungary. Overall, we identify these areas to be risk areas for urban sprawl for future research to focus upon.

6 CONCLUSION

Our maps presented in chapter 5 display areas with an “above average risk” of adverse land use related impacts. Areas with a high share of urban land experience significant hydrologic and mesoclimatic changes (excessive urban runoff, heat island effects) due to the spatial concentration of impervious surfaces. These areas are also characterized by a scarcity of valuable open space – both in absolute terms and per capita – and a quantitative loss of prime agricultural land and wildlife habitats. Regions or subregions with an irregular, dispersed and discontinuous urban form may be affected by a reduced efficiency of public transport systems and urban infrastructures (roads, water supply, sewer systems) and a higher per capita energy consumption (as an effect of larger travel distances). Furhtermore, areas with significant “pattern sprawl” as indicated in figure 7 witness higher risks of threats to endangered species due to landscape fragmentation and the high level of habitat disturbance.

At the same time, our analysis depicts “success stories” of implementing sustainable land use policies across the European Union. Examples refer to the relatively compact urban form and growth in parts of The Netherlands and the United Kingdom notwithstanding a high level of population density and urbanisation in both countries. Figure 3 gives evidence of a significant South-North divide in the use of ecologically sensitive areas for urban purposes. More effective or established landscape planning schemes and higher standards of environmental impact assessement in Northern Europe may explain this observation.

Furthermore, the relatively low degree of urbanisation in large parts of Scandinavia, Spain, Greece, Scotland, Ireland and southern Italy must be seen as an important ecological resource to be carefully managed in the future.

The measurement concept presented in this paper creates a methodological framework for evaluating the success of future land use policies and landscape protections programs. We deliberately avoided developing a composite sprawl index that aggregates the impact dimensions discussed above. The problem we see is that different sprawl indicators tend to outweigh each other in the process of aggregation. Therefore we recommend the use of dimension related sprawl types attributed with a specific profile of environmental and economic problems (see figure 7). Taking this into account, type-specific anti-sprawl strategies and instruments could be implemented.

7 REFERENCES

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/ireus/publikationen/CORP2008_34.pdf

22 de agosto de 2012

QUE FORMA(S) URBANA(S) PARA AS CIDADES SUSTENTÁVEIS DO FUTURO?”

José Félix Ribeiro, Graça Ponte da Silva

Ciclo de Workshops “As Formas e o Funcionamento das Cidades e os Desafios da Sustentabilidade” organizado por Departamento de Prospectiva e Planeamento e Relações Internacionais (DPP) do MAOT e a Associação Nacional dos Empreiteiros de Obras Públicas (ANEOP) - Outubro de 2009 e Fevereiro de 2010

Embora o papel fulcral que as cidades têm desempenhado no progresso da humanidade seja um facto histórico inegável, paradoxalmente, elas tornaram-se fonte de degradação ambiental, de ruptura do equilíbrio entre população, recursos e ambiente. Será possível um modelo de desenvolvimento assente no crescimento das cidades e na extensão do modo de vida urbano que, simultaneamente, cumpra os requisitos da sustentabilidade? Isto é, uma civilização urbana poderá ser sustentável? E estará essa sustentabilidade condicionada pela forma urbana? São estas as principais questões abordadas neste capítulo.

...

Num documento publicado em 2006 “Urban Sprawl in Europe-The Ignored Challenge” a Comissão Europeia chamou atenção para importância crucial do padrão de urbanização para sustentabilidade, estabelecendo um nexo entre forma urbana, padrões de mobilidade e consumos energéticos que procurámos aprofundar e discutir para o caso português durante os três workshops deste Ciclo “As Formas e o Funcionamento das Cidades e os desafios da Sustentabilidade”.

Nesse estudo, recorda-se que a Europa é um dos continentes mais urbanizados da Terra, já que cerca de 75% da população vive em áreas urbanas. Contudo, o futuro urbano da Europa constitui um tema de grande preocupação. Mais de um quarto do território da União Europeia está actualmente consagrado a fins urbanísticos e em 2020 cerca de 80 % dos europeus viverá em áreas urbanas. Em 7 países, poderão mesmo ser atingidos os 90 % ou mais. Em consequência, a procura de terras no interior e na periferia das cidades está a transformar-se num grave problema. As cidades estão a expandir-se e reduzem-se as distâncias entre elas. Esta expansão ocorre um pouco por toda a Europa, motivada por estilos de vida e de consumo em mutação, e é comummente denominada expansão urbana. As provas disponíveis demonstram, de forma irrefutável, que a expansão urbana tem acompanhado o crescimento das cidades por toda a Europa ao longo dos últimos 50 anos.

Considera-se que ocorre expansão urbana quando a taxa de reconversão da afectação dos solos para fins urbanos excede a do crescimento populacional numa dada área e ao longo de um período de tempo definido. Hoje em dia, a expansão deveria ser justificadamente considerada como um dos mais importantes desafios comuns que a Europa urbana tem de enfrentar.

As áreas onde os impactes da expansão urbana são mais visíveis encontram-se quer em países ou regiões cuja densidade populacional e actividade económica são elevadas (vide o caso da Bélgica, Países Baixos, regiões sul e ocidental da Alemanha, norte de Itália, região de Paris) ou que apresentaram um vigoroso crescimento económico (vide os casos de Irlanda, Portugal, Alemanha de Leste e região de Madrid), sendo que é particularmente evidente em países ou regiões que beneficiaram de políticas regionais e de financiamentos comunitários.

É igualmente possível observarmos padrões de desenvolvimento económico na periferia de cidades mais pequenas ou em aldeias, ao longo de corredores de transporte, e em numerosas zonas litorais geralmente ligadas a vales fluviais.

O conjunto de forças subjacentes a estas tendências inclui aspectos micro e macro socioeconómicos: a qualidade dos sistemas de transporte, o preço dos terrenos, as preferências individuais em termos de habitação, as tendências demográficas, as tradições e restrições culturais e a capacidade de atracção são factores que determinam o desenvolvimento das cidades. Outro factor importante tem sido a aplicação das políticas de ordenamento tanto a nível local como regional, alimentada pelos fundos estruturais e de coesão da UE destinados a apoiar o desenvolvimento de infra-estruturas.

Pela sua natureza, as cidades são locais onde um elevado número de pessoas se concentra em áreas reduzidas. Esta característica apresenta evidentes vantagens em termos de desenvolvimento económico e social podendo mesmo, nalguns aspectos, ser benéfica para o ambiente – por exemplo, o uso do solo e o consumo de energia per capita tendem a ser menores nas áreas urbanas, em comparação com áreas que apresentam populações dispersas, enquanto o tratamento de resíduos urbanos e de águas residuais permite beneficiar de economias de escala.

Subsequentemente, os tradicionais problemas de saúde ambiental – desde a água potável imprópria ao saneamento básico inadequado e às fracas condições de habitação – praticamente desapareceram das cidades da UE.

Não obstante, a população urbana continua a experimentar problemas ambientais graves, tais como a exposição ao ruído, casos de poluição atmosférica com impacte elevado, gestão de resíduos, limitada disponibilidade de água potável e ausência de espaços abertos.

Por outro lado, as tendências que apontam para áreas urbanas novas e de baixa densidade (nas cidades da Europa, o espaço total consumido por pessoa mais do que duplicou nos últimos 50 anos) resultam em consumos mais elevados. Os transportes (mobilidade), em particular, permanecem um desafio crucial para a gestão e o ordenamento urbanos. O impacte das infra-estruturas de transportes faz-se sentir de diversas formas sobre a paisagem. A impermeabilização dos solos (que faz aumentar os efeitos das cheias) e a fragmentação de áreas naturais são duas delas.

Mobilidade e acessibilidade, sendo factores determinantes na coesão do território europeu, são também elementos essenciais na melhoria da qualidade de vida das comunidades. Face à previsão de que o número de quilómetros percorridos em áreas urbanas pelo transporte rodoviário aumente 40 % entre 1995 e 2030, se nada for feito, colocar-se-ão a curto prazo graves problemas de congestionamento rodoviário (com crescimento significativo dos custos imputáveis a este fenómeno).

Assim, o planeamento de infra-estruturas de transportes, mais do que a construção de quilómetros de vias rodoviárias e ferroviárias, deve fazer parte de uma abordagem global que leve em conta o impacte real do investimento.

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.dpp.pt/Lists/Pesquisa%20Avanada/Attachments/3221/Ciclo_Formas_Funcionamento_Cidades_Doc-sintese.pdf

Ciclo de Workshops “As Formas e o Funcionamento das Cidades e os Desafios da Sustentabilidade” organizado por Departamento de Prospectiva e Planeamento e Relações Internacionais (DPP) do MAOT e a Associação Nacional dos Empreiteiros de Obras Públicas (ANEOP) - Outubro de 2009 e Fevereiro de 2010

Embora o papel fulcral que as cidades têm desempenhado no progresso da humanidade seja um facto histórico inegável, paradoxalmente, elas tornaram-se fonte de degradação ambiental, de ruptura do equilíbrio entre população, recursos e ambiente. Será possível um modelo de desenvolvimento assente no crescimento das cidades e na extensão do modo de vida urbano que, simultaneamente, cumpra os requisitos da sustentabilidade? Isto é, uma civilização urbana poderá ser sustentável? E estará essa sustentabilidade condicionada pela forma urbana? São estas as principais questões abordadas neste capítulo.

...

Num documento publicado em 2006 “Urban Sprawl in Europe-The Ignored Challenge” a Comissão Europeia chamou atenção para importância crucial do padrão de urbanização para sustentabilidade, estabelecendo um nexo entre forma urbana, padrões de mobilidade e consumos energéticos que procurámos aprofundar e discutir para o caso português durante os três workshops deste Ciclo “As Formas e o Funcionamento das Cidades e os desafios da Sustentabilidade”.

Nesse estudo, recorda-se que a Europa é um dos continentes mais urbanizados da Terra, já que cerca de 75% da população vive em áreas urbanas. Contudo, o futuro urbano da Europa constitui um tema de grande preocupação. Mais de um quarto do território da União Europeia está actualmente consagrado a fins urbanísticos e em 2020 cerca de 80 % dos europeus viverá em áreas urbanas. Em 7 países, poderão mesmo ser atingidos os 90 % ou mais. Em consequência, a procura de terras no interior e na periferia das cidades está a transformar-se num grave problema. As cidades estão a expandir-se e reduzem-se as distâncias entre elas. Esta expansão ocorre um pouco por toda a Europa, motivada por estilos de vida e de consumo em mutação, e é comummente denominada expansão urbana. As provas disponíveis demonstram, de forma irrefutável, que a expansão urbana tem acompanhado o crescimento das cidades por toda a Europa ao longo dos últimos 50 anos.

Considera-se que ocorre expansão urbana quando a taxa de reconversão da afectação dos solos para fins urbanos excede a do crescimento populacional numa dada área e ao longo de um período de tempo definido. Hoje em dia, a expansão deveria ser justificadamente considerada como um dos mais importantes desafios comuns que a Europa urbana tem de enfrentar.

As áreas onde os impactes da expansão urbana são mais visíveis encontram-se quer em países ou regiões cuja densidade populacional e actividade económica são elevadas (vide o caso da Bélgica, Países Baixos, regiões sul e ocidental da Alemanha, norte de Itália, região de Paris) ou que apresentaram um vigoroso crescimento económico (vide os casos de Irlanda, Portugal, Alemanha de Leste e região de Madrid), sendo que é particularmente evidente em países ou regiões que beneficiaram de políticas regionais e de financiamentos comunitários.

É igualmente possível observarmos padrões de desenvolvimento económico na periferia de cidades mais pequenas ou em aldeias, ao longo de corredores de transporte, e em numerosas zonas litorais geralmente ligadas a vales fluviais.

O conjunto de forças subjacentes a estas tendências inclui aspectos micro e macro socioeconómicos: a qualidade dos sistemas de transporte, o preço dos terrenos, as preferências individuais em termos de habitação, as tendências demográficas, as tradições e restrições culturais e a capacidade de atracção são factores que determinam o desenvolvimento das cidades. Outro factor importante tem sido a aplicação das políticas de ordenamento tanto a nível local como regional, alimentada pelos fundos estruturais e de coesão da UE destinados a apoiar o desenvolvimento de infra-estruturas.

Pela sua natureza, as cidades são locais onde um elevado número de pessoas se concentra em áreas reduzidas. Esta característica apresenta evidentes vantagens em termos de desenvolvimento económico e social podendo mesmo, nalguns aspectos, ser benéfica para o ambiente – por exemplo, o uso do solo e o consumo de energia per capita tendem a ser menores nas áreas urbanas, em comparação com áreas que apresentam populações dispersas, enquanto o tratamento de resíduos urbanos e de águas residuais permite beneficiar de economias de escala.

Subsequentemente, os tradicionais problemas de saúde ambiental – desde a água potável imprópria ao saneamento básico inadequado e às fracas condições de habitação – praticamente desapareceram das cidades da UE.

Não obstante, a população urbana continua a experimentar problemas ambientais graves, tais como a exposição ao ruído, casos de poluição atmosférica com impacte elevado, gestão de resíduos, limitada disponibilidade de água potável e ausência de espaços abertos.

Por outro lado, as tendências que apontam para áreas urbanas novas e de baixa densidade (nas cidades da Europa, o espaço total consumido por pessoa mais do que duplicou nos últimos 50 anos) resultam em consumos mais elevados. Os transportes (mobilidade), em particular, permanecem um desafio crucial para a gestão e o ordenamento urbanos. O impacte das infra-estruturas de transportes faz-se sentir de diversas formas sobre a paisagem. A impermeabilização dos solos (que faz aumentar os efeitos das cheias) e a fragmentação de áreas naturais são duas delas.

Mobilidade e acessibilidade, sendo factores determinantes na coesão do território europeu, são também elementos essenciais na melhoria da qualidade de vida das comunidades. Face à previsão de que o número de quilómetros percorridos em áreas urbanas pelo transporte rodoviário aumente 40 % entre 1995 e 2030, se nada for feito, colocar-se-ão a curto prazo graves problemas de congestionamento rodoviário (com crescimento significativo dos custos imputáveis a este fenómeno).

Assim, o planeamento de infra-estruturas de transportes, mais do que a construção de quilómetros de vias rodoviárias e ferroviárias, deve fazer parte de uma abordagem global que leve em conta o impacte real do investimento.

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.dpp.pt/Lists/Pesquisa%20Avanada/Attachments/3221/Ciclo_Formas_Funcionamento_Cidades_Doc-sintese.pdf

21 de agosto de 2012

O que faz Paris ser Paris e não Praga, Barcelona, Nova Iorque ou Londres

Nicolau Ferreira

15.08.2012

As ruas de Paris têm elementos que se repetem de bairro em bairro e que a tornam uma cidade única (Guillaume Plisson/AFP (arquivo))

...

Cientistas da Universidade Carnegie Mellon, em Pittsburgh, nos Estados Unidos, trabalharam dados visuais do Google Street View à procura de características distintivas de 12 cidades, entre as quais a capital francesa. E afinal, O que faz com que Paris se pareça com Paris?

...

o investigador diz que este programa pode vir a influenciar a urbanização. “Um software que for construído a partir do nosso pode ajudar os arquitectos a compreender o estilo das cidades para onde desenham edifícios e levar o público a apreciar o estilo e a história da sua própria região. Nesse caso, os construtores passariam a dar mais atenção ao estilo de uma cidade e a mantê-lo.”

...

Há também um contexto histórico que os autores defendem que estes resultados podem elucidar. Muitos elementos arquitectónicos que o programa identifica são partilhados entre algumas cidades. De certa forma, este padrão responde à questão de como um lugar acabou por ser como é. “Há uma narrativa estilística que começa na Grécia antiga e que se move tanto no espaço como no tempo, primeiro para Roma, depois para França, Espanha e Portugal, e finalmente para o Novo Mundo”, explica Alexei Efros. Ao identificar esses elementos arquitectónicos partilhados, poderá descobrir-se até a“história de outras influências, subjectivas e difíceis de quantificar, entre estes locais”.

...

Link para o texto integral:

http://www.publico.pt/Ciências/o-que-faz-paris-ser-paris-e-nao-praga-barcelona-nova-iorque-ou-londres--1559174?all=1

15.08.2012

As ruas de Paris têm elementos que se repetem de bairro em bairro e que a tornam uma cidade única (Guillaume Plisson/AFP (arquivo))

...

Cientistas da Universidade Carnegie Mellon, em Pittsburgh, nos Estados Unidos, trabalharam dados visuais do Google Street View à procura de características distintivas de 12 cidades, entre as quais a capital francesa. E afinal, O que faz com que Paris se pareça com Paris?

...

o investigador diz que este programa pode vir a influenciar a urbanização. “Um software que for construído a partir do nosso pode ajudar os arquitectos a compreender o estilo das cidades para onde desenham edifícios e levar o público a apreciar o estilo e a história da sua própria região. Nesse caso, os construtores passariam a dar mais atenção ao estilo de uma cidade e a mantê-lo.”

...

Há também um contexto histórico que os autores defendem que estes resultados podem elucidar. Muitos elementos arquitectónicos que o programa identifica são partilhados entre algumas cidades. De certa forma, este padrão responde à questão de como um lugar acabou por ser como é. “Há uma narrativa estilística que começa na Grécia antiga e que se move tanto no espaço como no tempo, primeiro para Roma, depois para França, Espanha e Portugal, e finalmente para o Novo Mundo”, explica Alexei Efros. Ao identificar esses elementos arquitectónicos partilhados, poderá descobrir-se até a“história de outras influências, subjectivas e difíceis de quantificar, entre estes locais”.

...

http://www.publico.pt/Ciências/o-que-faz-paris-ser-paris-e-nao-praga-barcelona-nova-iorque-ou-londres--1559174?all=1

20 de agosto de 2012

RE•ARCHITECTURE - RE•cycle, RE•use, RE•invest, RE•build

Exposição no Pavillon de l'Arsenal, Paris

Quando:

12/4/2012 > 20/8/2012

Onde:

Paris - Pavillon de l'Arsenal

The Pavillon de l’Arsenal has invited fifteen European agencies that question the way that modern-day cities are built to participate in this exhibition. Through their original strategies, these architects enact change upon cities which in turn impact on city-life.

...

Contemporary cities require a dynamic, lively and attentive approach, which, everyday, are fuelled by dialogue and shared experiences.

...

With the Re.architecture, Re.cycle, Re.use, Re.invest, Re.build exhibition we welcome an extremely promising generation of European architects who engage in participative and cross-cutting urban and architectural practices.

...

Presentation of the exhibition

...

The projects, in the form of micro-interventions or urban strategies, tend to turn unused land and buildings into opportunities. They breathe optimism into areas which have lost their sparkle: urban infills, waste lands, abandoned land or buildings or even large structures. They reclaim space at a time when European cities must be rebuilt and the sprawl contained. And, of course, they commit to saving that which is not renewable and reuse what can be recycled.

In light of such an unexpected, thought-provoking production, six people bear witness to this alternative urban approach through their own experiences: Jean Blaise, Michel Cantal-Dupart, Didier Fusillier, Guillaume Hébert, Maud Le Floc’h and Thierry Paquot. With festive, sustainable, responsible and environment-friendly cities - they each reveal the new time-frames of urban projects, order expectations and new tools implemented in new methods.